Update from Slate

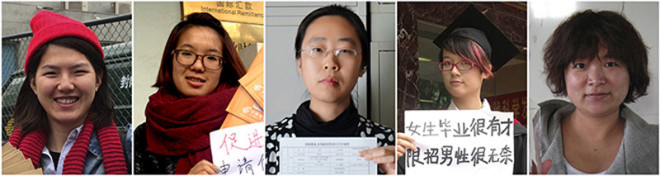

After more than a month of imprisonment, the so-called “feminist five” (Wang Man (王曼), Li Tingting (李婷婷), Wu Rongrong (武嵘嵘), Zheng Churan (郑楚然), and Wei Tingting (韦婷婷) were released from custody by Chinese police yesterday. The five activists had been arrested on March 8, International Women’s Day, over a campaign they attempted to organize online to hand out fliers on buses and subways in several cities calling attention to sexual harassment and groping in China.

That may not seem like much of a crime, even in China—they were arrested for “picking quarrels and creating a disturbance”—but the planned action took place at the same time as the so-called “two meetings,” the annual high-profile gathering of China’s rubber-stamp legislature, during which authorities are highly sensitive to any provocation. The arrests have also been read as a blunt message from the increasingly autocratic Chinese government to civil society groups.

The arrest of the activists is less surprising than the fact that they were released. (They’re not out of the woods yet. They’ll be under a form of restricted and monitored release, which was also used on artist Ai Weiwei after his highly publicized arrest and release in 2011.) The case sparked international outrage and drew condemnations from prominent figures including John Kerry and Hillary Clinton. But China has brushed off similar international criticism of its human rights practices in the past. So why did it back down this time?

For one thing, the case provoked an unusual amount of internal criticism. The five activists, all in their 20s and 30s, included some of China’s best known women’s rights campaigners, famous for performance-art style actions like occupying men’s restrooms to protest the unequal ratio of available stalls, shaving their heads to protest unequal university admissions requirements, and wearing red-splattered wedding gowns to draw attention to domestic violence. While not exactly encouraged by the authorities, feminist activists, challenging social conditions or even particular laws rather than the government itself, haven’t faced the same level of repression as campaigners on other issues. If the women had been handing out fliers about Tibet, Xinjiang, or Falun Gong, this would be a very different situation. But public pressure, both international and domestic, can have results on issues not considered national security concerns by the Chinese authorities.

The case was also particularly embarrassing for China, which is due to co-host a U.N. meeting on women’s rights in September. The meeting will mark the 20th anniversary of the 1995 Beijing summit at which Clinton, then first lady, delivered a forceful and well-remembered speech on women’s rights. China would presumably prefer that problems like forced abortions and the shaming of so-called “leftover women” not be in the global spotlight ahead of the meeting.

Joshua Keating is a staff writer at Slate focusing on international affairs.

For more information, go to http://www.hrichina.org/en/supporting-womens-rights-china